The language experience, or the lived experience of language

On embodied language and our personal language biographies

Let’s start with an exercise.

Draw an outline of a person, or print a template. Grab some colourful pencils, and find a place to sit comfortably and colour on paper.

Think about all the languages you speak. You may think of language as the traditional separation implies(English, German, Italian etc.), but you can also think of all the ways you have to communicate in the world that mean something to you: your dialect, situated or domain language, slang or any linguistic variation.

Where would you place those languages in the outline? You can think of where in your body you feel a language, but you can also think of the symbolic nature of body parts.

Try to approach this task intuitively, without overthinking. Once you start, you will see that you will find more partitions than you initially thought, and that, indeed, some languages will feel more “right” in one place than another.

Enjoy! As always, I would love to hear about it or see your outline if you feel comfortable. Read on to put this exercise into the context of the language experience.

The language experience

The exercise above, called linguistic portrait is created by one of my favourite researchers, Brigitta Busch, to aid the visualisation of one’s linguistic repertoire.1

I found her work while researching the interplay between multilingualism and trauma for a term paper, which I ultimately named “Multilingualism and its trauma coping potential”2. I ravenously read her publications, and I would’ve just stayed there if it wasn’t for the scientific necessity of showing a broader range of work.3

One of the key concepts in Busch’s work is the language experience, or “Spracherleben”.4 The language experience describes the perspective a person has on their own language use, incorporating three dimensions: bodily, emotional and historical-political. 5

The language experience gains an extra layer, but also increased visibility when we discuss it in the context of the language repertoire, especially if we consider the extended definition of it.6 Bush often mentions that “no one speaks just one language”, and invites us to look at language outside of the borders of the traditional definition. As I mentioned above before drawing the portrait think in the direction of your dialect, situated or domain language, slang or any linguistic variation like class, group and community-rooted communication. This allows anyone to examine their lived experience of language in a more nuanced way.

To bring the academic definitions above back to the embodied and the personal, let’s take a moment to reflect on these several questions:

When you consider the languages you speak(think about the extended definition above), can you notice differences in how it feels to use them or exist in spaces where they are spoken?

What does your body tell you when you think about the lived experience of each of them?

Is any of the ways you express yourself or the languages you speak penalised in some way by society? Does any of the languages have political turmoil or oppression woven into them or the fabric of your community? How does that affect you?

Do you speak a minority language, or are you an immigrant or refugee? What kinds of feelings arise when you compare the lived experience between the majority language and your first? How do the different environments you are in impact those language experiences?

These are just some questions to help you explore the lived experience of language in your own context and by no means a definitive exploration list. If I talk to each person who reads this article, we would have as many different stories.

Our stories, our language biographies

The exercise of drawing our language portrait helps us explore our language repertoire and situate it in our embodied experience.

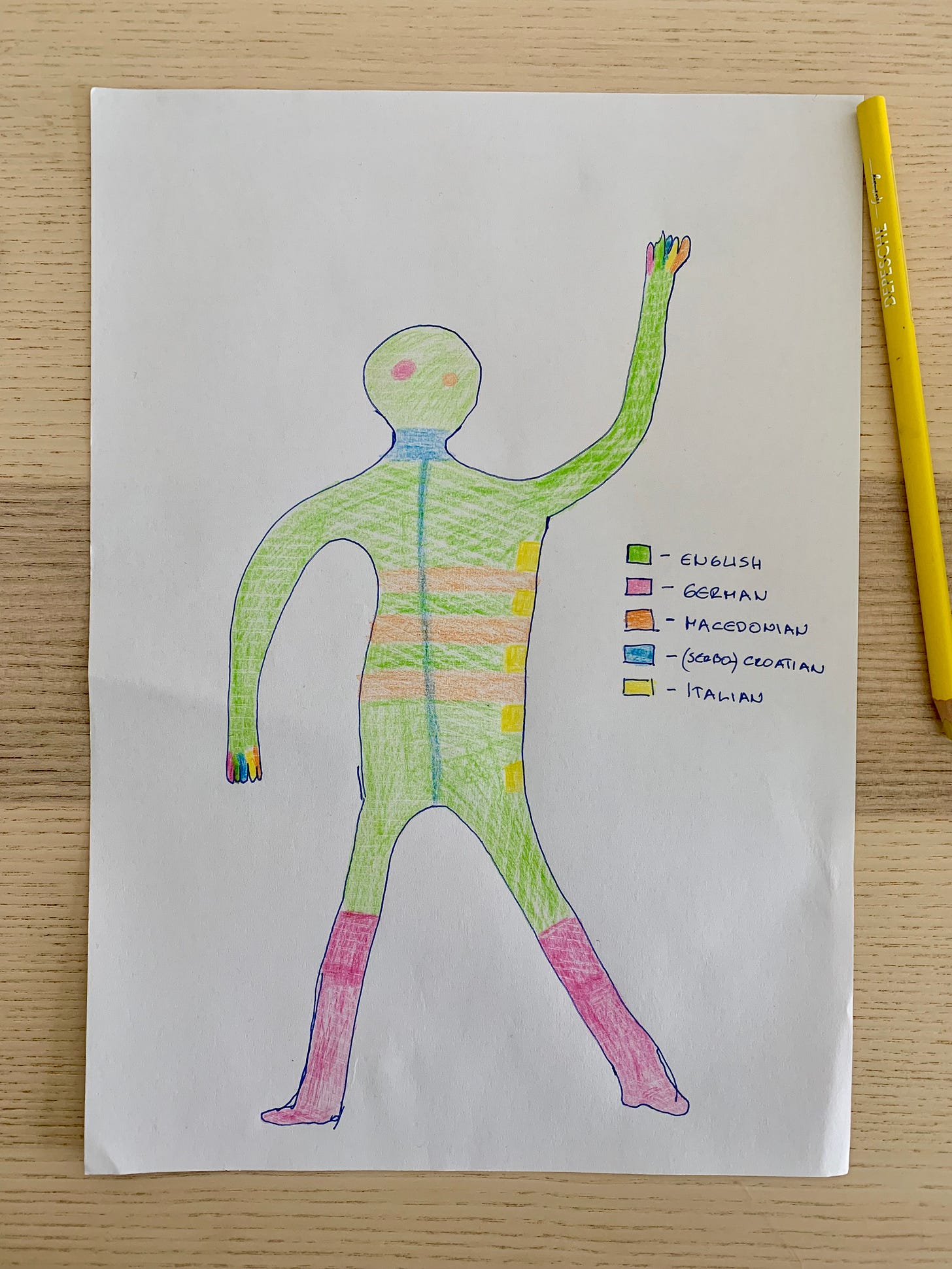

Seeing my linguistic portrait above after it was done feels incredibly vulnerable. I stuck to a few languages that I speak that are very traditionally separated and the repertoire certainly doesn’t include the full picture, but nevertheless, it felt as if one can learn so much about me by just looking at it.

The overwhelming majority of the body is covered in green, representing English. I started learning English when I was about 5 years old. My whole work life has been in English and a big part of my education. Our main household language is English, and I speak English to almost all my friends. The culture I consume (and produce) is also in English. In the image, it covers most of my head, my arms and the majority of my body, with the other languages intercepting its dominance occasionally.

German ended up being mostly represented as chic pink boots, but what I wanted to say with it is that German is for me a way to get places. German is the majority language of the country where I live, and is the language of institutions, school administration for my child and Uni for me, doctors and hospitals, everyday shops and necessities. However, I am utterly in love with the freedom of compound nouns and there are whole domains of my life that exist only in German(like baby stuff). I also often consume German literature, culture and political essays. Parts of my thinking regularly default to German because of all of it, and you can see a speck of pink in the head part of the silhouette.

Macedonian is represented by orange. I was born in Yugoslavia, but I grew up in Skopje, Macedonia. My primary and high school education was in Macedonian. My childhood and youth were lived in Macedonian. Because of that, you can see it as a core part of the body outline - remove those stripes in the middle and the whole outline would fall apart. These days I speak Macedonian rarely, and almost exclusively to my friend Monika, who keeps this world alive for me. I rarely think or express myself in Macedonian, but you can still find a speck of it in my head as I default to it when counting, or when grasping for names of concepts that you only learn young.

Blue is (Serbo-)Croatian. A part of my family is from Croatia, including my grandmother in whose house I lived when I was born for a few years and who took care of me often as a child. Another large part of the family is spread across ex-Yugoslavia. Having an extended family that switched between the large diversity of (language-)dialects as a child was normal, and I didn’t know otherwise. My mother didn’t grow up speaking Macedonian at home, but both parents stuck to speaking Macedonian to us. However, all the lullabies, songs and overall culture I learned as a child weren’t in Macedonian. One time, during the peak (post-)war times, during a summer in Croatia, with pouring sunlight, joyous pool screeches and cousins around me, I switched to Croatian not thinking much to ask my father something. He threatened me never to speak that language to him again, and I knew better than to defy it. The sun dimmed, the screeches softened, and the words got forever stuck in my throat. They still stay there, as you can see in the portrait, but they also run down my spine from there and make me who I am.

The small yellow squares represent Italian, the language my husband grew up speaking, one of the languages my son speaks, and the language of the world of my in-laws. I have absorbed pieces of the language and culture as part of my whole, much like the drawing shows.

You can see that my fingers are multicoloured, representing that I use all the languages as a toolbox. I interchangeably use them every day to express myself and communicate with others, often gladly mixing it all together.

I outlined my personal story as one of the many case studies I read, as it felt only fair. My personal language biography reveals all the aspects of the language experience: the bodily, the emotional and the historical-political. Language isn’t neutral, and the switching to the multimodal exploration(visual + narrative) that are the language portraits allows us to disrupt the usual way of thinking and bring to the foreground the elements of emotion, power relations and desire.7

The language experience and the (inner) world

In her book “Mehrsprachigkeit”(translated: Multilingualism)8, Busch mentions an interesting case that sheds more light on her premise that “no one is monolingual”. Busch talks about a high-school student from Germany who transitioned from her village to a school in the city. The student felt deficient when she compared her everyday language with the language used at school, namely the more revered, standard “Hochdeutsch”. The language divide was further stretched by the difference in class origins. Busch discusses that people develop negative self-perception when they are perceived by the environment as “other(different)-speaking”, and refers to the story as an example of how language can be used to exclude and marginalise individuals. The wider literature often situates school as the first space to produce this language-based otherness for many interviewees.

The student talks about her desire to fit in: „I still remember today how I would hear myself speak und and feel like an actress, what I said sounded so inauthentic to me.“ (own translation from German)

This perception, as we can see in this aspirational case, can make us strangers to ourselves. If you are an immigrant, you may find traces of this in subduing your cultural expressions and communication manner to fit the new standard, leaving you with a dissociated and drained feeling.

Language is intertwined with our experience of the world, our internalisations of it and our memories. One of the interesting case studies I found while researching the usage of multilingualism in a therapy setting, was the clinical case of a Corsican patient in Germany that Busch documented9. The patient, otherwise stable, would become severely upset upon her childhood trauma triggers. As part of the therapy, she was asked to speak to her inner child and tell her that she is in Germany, in the present, and that she is safe. When that wouldn’t work, the therapist asked what language she spoke to that inner child. The patient answered that she speaks German. When asked to switch to Corsican, the intervention worked - the symptoms reduced, the triggers subsided and the therapy could continue.

Another study examined the processing of traumatic memories by bilingual individuals.10 The participants were Spanish-English bilinguals who had immigrated to the USA and learned English as their second language. The researcher asked them to recall a traumatic memory from their lives and talk about it in Spanish and English. After the memory narration and retrieval, the participants needed to rate the intensity of the PTSD symptoms. The study results showed a significantly higher intensity of symptoms when the participants described the event in their first language, Spanish, and a more considerable emotional distance when they narrated the event in their second language, English. While that specific study ends with a conclusion that processing of the traumatic memories worked better in the first language, that conclusion in challenged by studies that show that the memories can be best processed in the language they were encoded11, reinforcing the idea of a strong relationship between language and our experience of the world.

There is even some evidence that language can impact our processing of sensations.12 13

The lived experience of a language can influence our perceptions of the world, and our perceptions of the world can impact our lived experience in a language.

I am called here to discuss the serious impact of language used as a tool of oppression, often enforced by language policies14 inspired by language ideologies15. This includes the silencing and loss of voice and ultimately the negative language experience that the oppressed experience, but also all the minor ways this impacts all of us every day. I will discuss these aspects in detail in the next article.

Some reflections to bring the theory discussed in this section closer:

Have you ever been confronted with that feeling of linguistic otherness as described?

Do you feel like you have more access to your memories, emotions or perceptions in one or the other language? Does that fluctuate and change over time?

Do you use linguistic strategies to protect or enable another side of yourself?

How language impacts language attrition and learning

The language experience can impact both language attrition and language learning/acquisition.

Language attrition describes the process of losing a language. A history of trauma can impact which languages are spoken and maintained.

Some ways in which language can stand in the centre of trauma and be an inseparable part of it:

..languages that are connected with the deep desire to identify and unite with someone else; languages of longing, from one, is separated by exile, oppression, voluntary or forced assimilation; languages from which one shies away for fear of exposing oneself or because one fears that they could compromise another, languages that one avoids and fears because they are connected with traumatic experiences, with the loss of autonomy and agency. (Busch & Reddemann, 2013, (own translation from German))16

Sometimes, a language is lost because of physical threats or as a direct consequence of a language policy of suppression(think colonialism). In some cases, even from a place of physical safety, the language experience is too negative to maintain the language. I read two studies17 18 that looked into the use of German by the Jewish community, both in the diaspora and in Israel.

A married couple who had known each other in Düsseldorf long before emigrating, when they were all but children, state that in more than fifty years of marriage they never spoke German to each other, not even intimately.”

And another informant says: "Among Jewish refugees like myself we only talk English, since it would seem too intimate to use German.”

...It thus seemed to me that the language which many of my informants had to reject not only embodied memories of Nazi persecution, but also of being loved and being secure within their own family.(Schmid, 2002)

Language learning can also be affected by the language experience. Bush mentions that, for immigrants, “adapting to a new linguistic environment can be a process of self-transformation, sometimes experienced as a loss of self.”19 Those complex feelings can paint the lived experience of a language and mark it as forced, an intrusion, and can make the process of learning painful.

However, a positive language experience can foster learning. To have a positive language experience, learners need experiences that allow them to build confidence in their abilities and positive self-perception. We need environments that promote a sense of belonging, competence, and joy in language use. A positive language experience can also prevent language attrition.

Closing remarks

Our language biographies are more complex than we think. Our lived experience of each of the languages we speak impacts our perception of the world and affects our efforts at language learning. Working on processing the emotional and bodily aspects, and keeping aware of the historical-political aspect of our language experiences can help us find peace and motivation along our learning (and life) journeys.

Did reading this change your perception of yourself as a language learner? I’d love to hear about it.

Peak ahead

The next article will discuss language ideologies, connect them to the language experience and further expand into its historical-political aspect.

Busch, Brigitta (2018). The language portrait in multilingualism research: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies 236, 2–13. [pdf]

A pdf is available here. I build heavily on the papers I read for it. However, I centre the language experience instead of trauma in this article.

A list of all publications, books and papers can be found on this website. Luckily, a lot of those are publicly available. However a lot of them are written in German, although there is enough to grasp her main research points in English, like the paper linked above.

Brigitta Busch, Expanding the Notion of the Linguistic Repertoire: On the Concept of Spracherleben—The Lived Experience of Language, Applied Linguistics, Volume 38, Issue 3, June 2017, Pages 340–358, https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv030

Busch, Brigitta; Reddemann, Luise (2013) Mehrsprachigkeit, Trauma und Resilienz. Zeitschrift für Psychotraumatologie 11, 23-33. [pdf]

Busch, Brigitta (2012) Das sprachliche Repertoire oder Niemand ist einsprachig. Vorlesung zur Verleihung der Berta-Karlik-Professur an der Universität Wien. Klagenfurt/Celovec: Drava. [pdf]

Brigitta Busch, The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited, Applied Linguistics, Volume 33, Issue 5, December 2012, Pages 503–523, https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams056

see 5th reference, I don’t know how to link to the same one twice (sorry^^)

Schwanberg, J. S. (2010). Does Language of Retrieval Affect the Remembering of Trauma? Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 11, 44-56.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15299730903143550

Marian, V., & Neisser, U. (2000). Language-dependent recall of autobiographical memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129(3), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.129.3.361

Gianola, M., Llabre, M. M., & Losin, E. (2020). Effects of Language Context and Cultural Identity on the Pain Experience of Spanish-English Bilinguals. Affective science, 2(2), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-020-00021-x

Boroditsky L. How the Languages We Speak Shape the Ways We Think: The FAQs. In: Spivey M, McRae K, Joanisse M, eds. The Cambridge Handbook of Psycholinguistics. Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology. Cambridge University Press; 2012:615-632.

Spolsky B. What is language policy? In: Spolsky B, ed. The Cambridge Handbook of Language Policy. Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics. Cambridge University Press; 2012:3-15.

Gal, S. (2023, June 21). Language Ideologies. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Retrieved 6 Nov. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/linguistics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.001.0001/acrefore-9780199384655-e-996.

definitely someone needs to teach me how to do this. reference 5 again :)

Schmid, M. (2002). First-Language Attrition, Use, and Maintenance. English and American Studies in German (2001), 2001(2002), 13-16. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783484431010.13

Betten, A. (2010). Sprachbiographien der 2. Generation deutschsprachiger Emigranten in Israel. Zur Auswirkung individueller Erfahrungen und Emotionen auf die Sprachkompetenz. Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik, 40(4), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03379843

see ref 6

Another insightful read! To be honest, I don't know if this changes how I see myself as a language learner but it's definitely making me think more deeply about it. I really love your exercise of representing language as a physical body part and that alone is making me analyze my own attachment and relationship to different languages. Thank you for sharing!